Books I Read January 16th, 2022

I had a lovely week, thanks for asking. Got a lot done, baked some good bread. Feeling energetic. Purposeful. Positive. Read the following books.

The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston – A compelling and bleakly funny account of growing up an impoverished Chinese immigrant in post-war San Francisco. As a rule I'm not big on the 'my family was absolute batshit' form of literary nonfiction and occasionally this gets a bit overheated, but basically I thought it was strong and weird and I dug it.

The March of Folly by Barbara Tuchman – I had basically completely forgotten the existence of Barbara Tuchman which is both weird cause I used to love her but kind of great cause I remembered how great she is. This is really first rate popular history, brisk and entertaining but also measured and thoughtful. Tuchman is an astute and atypical commentator even on events with which I was already pretty familiar, and she's genuinely funny, which is unfortunately a rare quality in historians. Fun stuff.

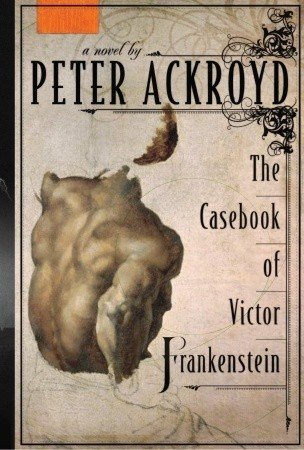

The Casebook of Victor Frankenstein by Peter Ackroyd – Entertaining if indistinct literary horror.

Bleak House by Charles Dickens – Last I dipped into Dickens I was 19 and found Great Expectations an absolutely ponderous melodrama but I don't put that much stock in the opinions I held at 19 (in retrospect American Beauty is a horrible movie) so I figured I'd give him another shot. Negs—the characterization is effective but one dimensional. This results in some engaging minor characters but the majors are pretty insufferable. It does that Victorian era thing (Jane Austen does this also) where a character is sketched in thumbnail as soon as they come onto the page ('Richard is so charming and kind-hearted but also inconstant, I hope terribly he doesn't find himself bogged down by this Jardyce inheritance') and then spending the rest of the book confirming this initial impression ('Poor Richard, so sweet and amiable, but alas his lack of direction has doomed him!'). Its mawkish—Esther is an absolutely insufferable Mary-Sue and her Guardian somehow even worse. Pros—Dickens is a masterful critic of his age, funny and savage with a core of genuine outrage. His ability to set a scene by turning a metaphor tighter and tighter over the course of a paragraph is fabulous. And he has a number of observations about dire poverty—and particularly about the street child Jo—which reminded me of my own experience working with the unhoused to an uncanny and frankly horrifying degree. It ain’t Dostoevsky, but I’d take it above Victor Hugo.