Books and Tunes End of April

Several days late, but I've had friends visiting the last ten days, and I've been busy going to tourist attractions and trying to make them jealous. Have you seen our avocado? They're amazing. We have beaches and mountains. Your Mexican food tastes like someone defecated into a rubbery tortilla. How do you live, man? How do you even get by?

These are the tunes I liked and the the books I read during the back half of April, 2019, a fine month, now sadly behind me.

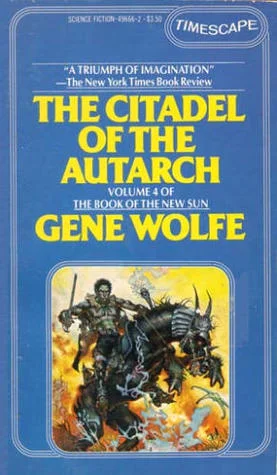

Book of the New Sun by Gene Wolfe – I picked up the first book of these, Shadow of the Torturer, from the Edgartown public library when I was twelve or thirteen, because it had cover where the hero held a sword, and that was the only sort of book I read when I was twelve or thirteen. A thousand pages later I was left in awkward awe at the journey; twenty years later, I feel similarly.

Book of the New Sun is, for my money, the only work of high fantasy which can be justly called literature. It functions, first of all, as an enjoyable if peculiar genre exercise; there are sword fights (lots of them! Good ones!) horrifying monsters, strange sorceries, etc. One can (and I imagine many have) give it a surface read and come away confused but generally having enjoyed the experience. But of course it is vastly more than that, a mad bildungsroman, a crookedly complex work of moral theology.

There is genuinely so much genius in this book that even a much larger review could not take adequate note of them; Wolfe gives himself joyful freedom to wander into strange corners of his imagination, and no one reading this book will soon forget his re-telling of the Minotaur's Labryinth or the Kipling's Jungle Books. Admittedly, these side adventures can feel somewhat jarring, coming from nowhere and disappearing as quickly. The narrative structure is peculiar to say the least, but the flip of that is you genuinely never know what's going to happen in the next chapter.

I could go on; the prose is masterful, with Wolfe's famously odd use of archaic language functioning to further unsettle the reader's directions. It's sexy and confusing and horrifying; it has my favorite magic sword in all of literature. But I frankly don't have the energy right now to give a proper review right now, so I'll end with just telling you to take a few weeks out of your life and work through it.

The Confessions of Nat Turner by William Styron – The stylized recollections of Nat Turner; slave, preacher, failed revolutionary, in the days leading up to his execution by the state of Virginia. Beautifully written, at once sympathetic and horrifying, a formidable attempt to conceptualize the limitless evil of American slavery. Very good.

The Laughing Monsters by Denis Lehane – An American intelligence agent and his frenemy, a native mercenary, get into trouble in Africa in what wants to be an updated Graham Green novel. It's...fine. It's not badly written, there are a few touches here and there that let you know Lehane has spent some time on the continent (the little baggies of high proof liquor, trying to find a working internet cafe), but it has some unnecessary stylistic flourishes and plot wise it doesn't hang together that well. Another one that doesn't seem to quite satisfy the conditions of high literature or effective genre stuff.

Down Below by Leonara Carrington – A description of the author's descent into madness and imprisonment in a Spanish insane asylum in this slim but valuable volume. The peculiar obsessions, the quasi-religious mania, the abiding sense of persecution, all have the undeniable ring of genuine insanity. It's good, but what's more astonishing than the book itself is having undergone this experience Carrington was capable of regaining sufficient sanity to write it.

Picture by Lillian Ross – The compelling tragedy of 1950's Red Badge of Courage, an ambitious attempt at high art torn down by a foolish public, a crass studio system, and the artists' own personal weaknesses. Ross works with fabulous restraint, chronicling the film from enthusiastic inception to sad failure, leaving the dramatis personae to reveal themselves in asides and casual comments. Being a Hollywood hanger-on myself these days, I probably got a particular kick out of the content, but this is thoroughly enjoyable even if you aren't having your face shoved daily into the fetid bowels of film making. Worth your time.

I Am Not Sidney Poitier – The childhood and youth of a man who is not, but looks quite a bit like, Sidney Poitier. Structurally this is maybe a little unsound, and it doesn't quite hang together perfectly, but on the other hand I think Percival Everett is a genuinely fabulous comic writer. There is a recurring bit about Ted Turner which had me howling pretty consistently, and felt more than worth the price of admission.

The Thief and the Dogs by Naguib Mahfouz – A thief gets out of jail, seeks revenge on his wife/friends in this noir/allegory for the disillusion of Egypt post-Nasser. It's competent but a little one note, and I'd be lying if I said I saw the sort of genius which I gather the author is generally credited. Maybe I'll try him again somewhere down the line.

Latin Blood – A selection of short mysteries from Latin American writers. Really I just picked this up because it was the only thing I could find in the LA library system with a story from H. Bustos Domecq, a joint pseudonym under which Borges and Adolfo Bioy Cesares wrote classic Holmes-style mysteries. Anyway it was fine, I don't really like this style of writing so I'm probably not the best person to render judgment on the quality of these particular iterations.

The Life and Death of Leon Trotsky by Victor Serge and Natalya Sedova – A biography of Soviet Russia's flawed hero by a man I regard as one of the better writers of the 21st century should probably be better than this. It's competent, but coming shortly after Trotsky's death seems to serve more as anti-Stalin propaganda than a genuine attempt to grapple with Trotsky's life. There's a (predictable) tendency to understate the horrors of the early portion of the Russian Revolution (Orlando Figes' A People's Tragedy offers useful counterpoint), and Serge is clearly reigning in the linguistic complexity and brutally honest observation which characterizes his best work.

Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima – A woman divorces her husband, raises a young child in 70's Tokyo. It's a pleasant read, generally well-written and with some clever stylistic contrivances, but it doesn't really go anywhere and ultimately it felt kind of ephemeral.

ZeroZeroZero by Roberto Saviano – A lengthy and ludicrously overwritten history of the cocaine trade. Saviano's self-obsession was clear in his earlier Gomorrah, but seemed excusable based on the scruffy first-person reporting to which he subjected himself, and the fact that his outrage, emotive and self-referential as it tended to be, was directed at the cadre of criminals actively corrupting his birthplace. It feels entirely out of place in ZeroZeroZero, which in practice is just a high-level take on the cocaine trade, of the kind any non-fiction writer might put out, interspersed with endless observations about Saviano's deteriorating mental state, tedious on its own merits and absurd given his distance from the subject. The last quarter in particular felt like being cornered at a party by someone on the eponymous narcotic, nodding along at their pointless and rapid speech until you can find some excuse to break away. Avoid.

Nothing but the Night by John Williams – A young man doesn't like his Dad, has a mental break down in 50's New York. An early work from a very talented writer, the material is strong but the scope is quite limited, particularly when compared against Williams' later work.

In Love by Alfred Hayes – A man narrates the story of his broken relationship to a woman at a bar. Short, pithy, powerful, anyone who ever experienced heartbreak (haven't you? What the hell have you been doing with your life?) will find themselves nodding along at Hayes's insight into the universal misery of said condition. Good stuff.

Amsterdam by Ian McEwan – Rich assholes behave badly, get their comeuppance. I preferred McEwan's straight nightmares to this rather flimsy attempt at satire, which, though readable and occasionally funny, is predictable and kind of sanctimonious.

Fifth Head of Cerberus and Other Tales by Gene Wolfe – A masterful suite of novellas about identity, 'humanness' and two planets in a distant solar system in some unknowable future. Each of the three somewhat interlinked stories are written in radically different styles, showcasing the extent of the author's genius. Each are strange and beautiful and frightening and sad. I've sad it before and I'll say it once more; Wolfe was one of the best writers of the 20th century. We lost a giant this month.

Once and Forever by Kenji Miyazawa – A collection of children's stories by what I gather is Japan's most beloved children's story writer. They're fine, they're good, I'd read them to a kid, it doesn't quite fall into that rare category of literature which works for children of 7 and adults of 35, but then again that's basically just Kipling.

Children's Act by Ian McEwan – A judge decides whether a teenage Jehova's Witness will get a blood transfusion. Sometimes it takes a couple of books to decide if you like a guy, and I think I don't really like Ian McEwan. He's a peculiar sort of middlebrow; the language is fine, its breezy and not awful, but he has the infuriating habit of writing a sentence of dialogue and then writing a paragraph explaining what that sentence is supposed to mean, which is always, always, always bad writing. And the ubiquitous nastiness (everyone is terrible, all decent-seeming acts are secretly done for selfish reasons or will result in some unanticipated awfulness) feels lazy and narratively unsatisfying, a performance put on for that sort of reader who assumes high literature has to be cynical.