Books I Read October 31st, 2019

At the moment the fires here in LA are not so much 'spooky' as they are 'nightmarish harbingers of a global apocalypse'. My Halloween costume is, 'Man in Suit', which, hey, I don't wear suits a lot, so for me they're kind of like a costume, just one that you don't need to purchase at a seasonal outlet store.

Morte D'Urban by J.F. Powers – A worldly member of a minor ecclesiastical order is sent to work at a modest retreat in a midwestern backwater, wearies of its unpleasant duties and banal personalities, struggles to reconcile his ambitions with the moral obligations of a man of the cloth. Less a book about God and more a book about priests, if that makes sense, far from the searing religious melodrama of a Power and the Glory, for instance. That said, it's solid work, the characters are well-drawn, not always likable but basically sympathetic. Small but well-made, let's say.

Hard Rain Falling by Don Carpenter – An orphan with anger control issues grows up on the streets, struggles to escape his destiny in a penitentiary and to become capable of love. Not quite a prison novel, there is a feel of authenticity to its Pacific Northwest poolhalls and juke joints, and a shaggy sort of structure which likewise seems to honestly depict the misadventures of a certain sort of protagonist, one outside respectable society but not given to the forms of vigorous criminality which make for melodrama. Sad but honest, strong stuff, worth your time.

Silence by Shusaku Endo – A Portuguese Priest sneaks into Shogunate Japan, tries to keep the gospel alive among converts being brutally hunted by the authorities, is forced to confront the depth and meaning of his faith. Fabulously strong stuff, a great psychological novel. The writing is neat but effective, the moral complexities of the situation feel uncomfortably and honestly messy, the characterization is fabulous. A strange, thoughtful, and sympathetic take on the demands of the righteousness and the nature of sacrifice. Very strong stuff, deservedly venerated.

My Friends by Emmanuel Bove – A cowardly, ineffectual everyman searches for understanding in the back streets of Paris. I read it late at night in an airport and confess it didn't leave much of an imprint.

The Moon and the Bonfire by Cesare Pavese – Returning to the Italian countryside in which he was raised an impoverished orphan, our unnamed protagonist loosely investigates the fascist history of his village, discovers death, brutality and betrayal. Combines a wistful, Proustian sort of nostalgia for youth and love and passion mixed with an effective, oddly believable mystery. Sly and subtle, good stuff.

On the Abolition of All Political Parties by Simone Weil – Simone Weil thinks it would be better if democracies didn't have official parties, is probably right, doesn't have any real clear on idea on how to set that up practically. Weil was a fascinating and admirable character, but there's not a ton of meat on this bone.

Rock Crystal by Adalbert Stifter – Two young children get lost in the Alps, in this slender, excellent work. The story is, obviously, very simple, but the writing is magnificently vivid, the descriptions of the glaciers and mountains being powerful enough to lower the reader's body temperature a few degrees. A lovely little fable.

The Life and Opinions of Zacharias Lichter by Matei Calinescu – Tales of a Bucharesti holy fool and his attempts to live entirely free of cant or dishonesty and in naked service of the immediate reality of existence. Records of his speeches, stolen snatches of his poetry, depictions of the strange friendships and enmities which he has formed, largely without any sort of story. Obviously this sort of thing lives or dies on the naked strength of the author's prose and thought, and Calinescu proves himself the rare sort of talent who can manage this kind of novel. Lichter himself is a strange delight, a modern day Diogenes who rejects all forms of insincerity, down even to memory, in favor of a furious attachment to a sort of pre-conscious conception life itself. I thought it was funny and moving and thoughtful, though I concede it won't be to everyone's taste.

Alfred and Guinevere by James Schuyler – The story of two young siblings, told in diary entries and snatched of dialogue. Schuyler has a great talent for depicting the passionate and confused state of childhood, its jealousies, passions and follies. The structure alone is worth your trouble.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf – Props to Marlon James for just straight up writing an epic fantasy, but this didn't do it for me.

The Old Man and Me by Elaine Dundy – An American party-girl with a dark secret seduces a middle-aged Englishmen of modest renown. A lot of the Anglo-American feuding kind of bored me, and in general I didn't feel like the comic prose was as funny as it should have been. The noirish bits are much more interesting, but like in The Dud Avocado Dundy ultimately shies away from it, committing to a less interesting romance that ends kind of neatly.

Blindness by Henry Green – A tragic accident blinds a gadabout public school boy, messes with his family and loved ones, highlights the broader tragedy of the human condition. Green wrote this when he was still in undergrad, and it kind of reads like it. He's still a clever writer but this is kind of over-emotive line to line, a far cry from the devilish (sometimes exaggerated) subtlety of his other works.

Duffy by Dan Kavanagh (Julian Barnes) – A bisexual private detective investigates blackmail. Competently but unexceptional.

The Bitter Honeymoon and Other Stories by Albert Moravia—Italian men of various ages make poor decisions while in love. Well-written and engaging, if fixated on a fairly singular theme.

Mona Lisa Overdrive by William Gibson—The final book in Gibson's Sprawl Trilogy sees a collection of addicts, celebrities and general losers caught up in a lots of criminal/corporate shenanigans, an AI singularity. The weakest of the three, but still strong, and as a whole I have to say these are pretty masterful. The setting is enormously clever, and Gibson has a gift for pacing and structure, lots of fast moving stories a-typical to the genre but still fairly action packed. He's also a genuinely good writer; he knows what not to say, and for all the metal arms and weird guns this is a deeply wistful quality to the story, a patina of sorrow which hangs over the story without overwhelming it. One of the handful of truly excellent works of sci-fi ever written.

A Posthumous Confession by Marcellus Emants—A chronically miserable misanthrope details his pointless life and terrible crimes in this confessional novel lying somewhere between Dostoevsky and Jim Thompson. Why are some men better than others? Are we constitutionally equipped for certain behavioral patterns, and if so, does this inborn identity not make a mockery of conventional morality? The confessional novel as a subgenre can get tiring pretty quickly, bogging down in endless description of petty grotesques, but Emants manages to pull it off pretty fabulously. The writing is lucid is bitter, the questions being asked thoughtful and sincere. Really very good, if, obviously, quite grim.

In Parenthesis by David Jones—An epic poem in the style of the Mabinogi detailing a company of Britishmen being slaughtered on the Somme. Genuinely masterful. The writing is sonorous and madly complex, rich with strange and disturbing imagery, colloquial conversation interwoven with allusion to myth and legend. It all serves to turn the comparatively familiar image of a WWI battlefield into a world that seems as alien as outright fantasy, treating war as a foreign country, horrifying and in some ways beautiful. Unquestionably a masterpiece, difficult but well-worth your time.

Miserable Miracle by Henri Michaux—A frenchman details his experiences with narcotics. I've never really understood the tendency people have of imagining that hallucinogens provide some pathway towards a more 'authentic' experience of reality, as if deliberately taking a substance the explicit purpose of which is to corrupt and distort your thought might lead to genuine insight. For that matter, Michaux seems like kind of a bullshitter. His depictions of the effects of eating hash, in particular, are so baffling peculiar as to make one question his veracity more generally; in thirty-five years I have never, ever heard of anyone having had 'visuals' from marijuana, and remain skeptical at the five pages or so he dedicates to his own fever-dreams after eating an undisclosed amount of 'Indian hemp', as he calls it. Ultimately, this has not done much to break my general opinion that there is nothing duller than listening to someone brag of their drug use.

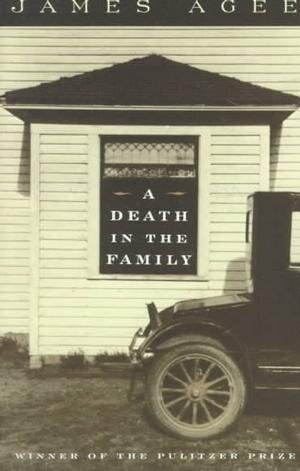

A Death in the Family by James Agee—The unexpected death of the patriarch of a Knoxville family thrusts his child, wife and other relations into a desperate reconsideration of their own lives and limitations. A kaleidoscopic rumination on the weight, purpose and essential tragedy of family. Sad and lovely,

Consider Phlebas by Iain M. Banks—Far future space opera shenanigans. Not for me.

Green Mansions by W.H. Hudson – A Venezuelan revolutionary escapes to the jungles of Guyana, falls in love with a forest nymph. A throwback romance which seems more appropriate to 1890 than 1940, and there's some icky ethnic stuff, but despite a general lack of originality that is a well-polished gem of a story. Its melodrama but all works, Hudson has a talent for bucolic description and its just weird and subtle enough to work.