Media I Consumed May 7th, 2018

A week of May in the books. We’re going from warm to hot here, the natives often warn me of the summer to come. There are many places in LA where there are no sidewalks and caught up in my thoughts I seem to find myself walking through a lot of them lately, up gulleys, skirting small highways. I haven’t been able to make myself watch a movie in a while, which mostly I blame on the frustrating awfulness of the Filmstruck interface. I hope you are well. The other you. That one, yes.

Last week I read the following.

Little Reunions by Eileen Chang – A fictionalized account of Chang’s youth in Shanghai and Hong Kong, as the last child of a fading, internationally oriented caste of Mandarins, with special emphasis on the relationship with her brilliant,, narcistic mother, and her fickle first lover who plays Quisling with the Japanese invaders. I was excited to read this, having really like the other stuff of Chang’s I read, but this was kind of disappointing. A lot of effort goes into trying to express the elaborately complex social relationships common to this era (there’s a lot of ‘First Uncle’s second concubine and I used to…’), but the narrative remains peculiarly narrow, and I kept hoping for a wider perspective which never really presented itself. She’s obviously talented, there are some savage little bits here and there, but the book feels goopy, like someone do a really deep dive into their familial dirty laundry without the narrative sharpening required for fiction. Disappointing.

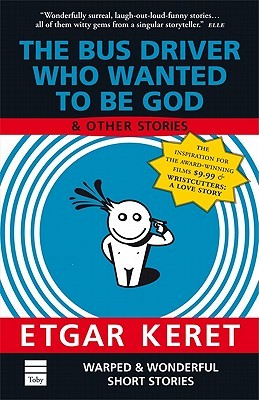

The Driver Who Wanted to be God and Other Stories by Etgar Keret – After last week’s somewhat disappointing snatch of Keret’s non-fiction it was fun to read him back in top form. I’m honestly shocked that Keret isn’t more popular than he is already—not only are his stories funny, poignant, and original, but they’re also simple and short. One of those rare books that can be enjoyed by people who like to read and people who don’t really like to read.

The Mexican Revolution by Adolfo Gilly -- The thing about Communism is that it lost—which, counter to both Marxist theory itself and later self-serving capitalist critiques, doesn’t prove anything, because there’s no inevitable march of history, no absolute law to anything, sometimes dice just roll a certain way—but it does make reading communist histories feel like picking through the sacred texts of some decayed and largely forgotten religious order. Maybe it always kind of felt like that. Certainly, a great deal of the intellectual force of Communism (apart from just generally being right about a lot of things) was that it relied upon a vocabulary and a general framework which only true believers would bother to learn, the use of which served (and still serves) to off-foot an opponent. This, naturally, led to the development of a style of leftist writing which is academic at its worst – verbose, needlessly dry and dogmatic. Is there such a thing as a first rate communist historian? That’s a serious question, please answer in the comments.

Anyway that rant aside it’s been so long since I read anything about the Mexican Revolution that I was basically coming in blind, and it is a pretty fascinating bit of human history, and so I didn’t mind this, but even when I found myself in intellectual sympathy with Gilly I was also somewhat bored. Like, ‘yes, of course, the exploitation of the rural peasantry by the Conventionist Bourgeois forces was an inevitable consequence of the Morales’ commune’s failure to extend their anarcho-rural template to the urban masses,’ but also this is pedantic and duller than it should be.

Late Fame by Arthur Schnitzler – Saxberger is an aging civil servant whose stasis is interrupted by the discovery that a book of poems he wrote in his half-remembered youth has become the ur-text for a movement of struggling Viennese artists. A funny, poignant, clever meditation on the vanity of intellectuals and the essential pointless absurdity of fame. Swift, lovely, shockingly modern given it was written more than a century ago, I’m a sucker for anything which mocks the arrogance of my caste but even those of you engaged in more valuable occupations than writing fiction will likely find this worth your time.

The Juniper Tree by Barbara Comyns – A working class woman’s attempt to create an independent life with her young daughter are interrupted by the affectionate attentions of an upper class couple. I really hesitate to give much more description of the narrative than that, other than to say that Comyns is the genre-bending feminist hiding beneath your bed, whispering terrors from with the black depths of bourgeoise, patriarchy induced ennui. That prose got pretty purple there but my recommendation is entirely sincere. I wish I could discuss it more without spoiling it, but I kind of can’t.

The Underdogs: A Novel of the Mexican Revolution by Mariano Azeuela -- While serving as a doctor in the Northern Division Azeuala somehow found the time to dash off this formally complex but brutally raw novel about the Mexican revolution, from its early, idealistic period to its moral and military collapse. This is fabulous, beginning as a scathingly subtle satire of heroic military literature before taking an abrupt nihilistic turn, some fascinating amalgam of The Forty Days of Musa Dagh and Heart of Darkness. And to recap, he wrote all of this literally while it was happening—even Victor Serge had to sit on his stuff a while. Really, really good. Really mean.