Books I Read This Winter (Part 4)

We are very nearly, brace, yourselves I know this is going to be a lot for you to handle, but we are very nearly at the end of my long backlog of books that I read this winter and didn't get around to reviewing because I was traveling/lazy. Which is good because we're getting towards spring here in the Apple, which means I walk more and write more and listen to more music and wave to more handsome young woman and so on and so forth. Except that actually we had this unfortunate cold snap the last couple of days, had to bundle up tight but it will likely be the last time the weather will be apporpriate to eat Ramen for a while. Anyway, here are some books I read, feel free to not read this, and to go do something more valuable with your time, like hugging your children or staring at a wall.

Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen – If one picks up whatever 1000 page opus the critics have dubbed this months novel of the century, the one that pretty girls in stockings and dashing your men in berets are very conspicuously reading on the L-train and at happy hour, and one discovers that it is a mound of feces doused in diesel and lit on fire, one is unsurprised. People are not very intelligent, and the intelligent ones least of all. But somehow one feels differently when it comes to books widely regarded as classics – surely our parents were wiser than we, one hopes, surely the collected judgment of the ages cannot be wrong.

All of which is to say that I was very much expecting to like Sense and Sensibility. I will go one further – I was quite looking forward to liking Sense and Sensibility, if for no other reason than to spite my 16 year old sell who loathed Pride and Prejudice, there being few sensations in life more pleasant than contempt for a previous personal iteration.

Alas.

In the credit column for Ms. Austen – she could give a good burn. There are some very sharp lines in here, so subtle that you miss the insult for half a paragraph after you read it.

In the debit column is literally everything else.

Her characterization is absolutely deplorable. Every person is introduced with a thumbnail sketch which lays out in numbing detail the handful of qualities which will define every interaction with said character for the remainder of the book. Elinor is sober and serious! Marianne is headstrong and passionate! Willoughby is handsome and rakish! If you managed somehow to skip one of these introductions, worry not, they will be repeated a rough 100 times throughout the course of the narrative. The plot is at once mind-numbingly tedious and absurdly melodramatic. Each surprise is telegraphed with a bluntness which would shame a third-rate mystery writer, for who, having been told that Willoughby is untrustworthy literally a dozen times in the first 50 pages, would be surprised that his union with poor Marianne does not come off as hoped? For that matter, the tension in the book is largely maintained by one of those absurd Victorian-era conceits whereby two characters cannot stand to have a simple conversation with one another about the immediate events of their life though those two characters have the most intimate relationship with one another (See also: Victor Hugo). Even by the bizarrely formalized etiquette of the era, surely it is not so terribly pushing the lines of gentility for Elinor to at some point go, 'yo, sis, you married to that dude, or what?' But it never seems to happen.

In short, Mark Twain and I are of one mind on the issue – 'I go so far as to say that any library is a good library that does not contain a volume by Jane Austen. Even if it contains no other book '

The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro – This is my first Ishiguro, and the only thing I knew about it going in was that there was some dispute when it first came out over whether it was 'really' genre fiction or something else, which is the sort of question than only an absolute idiot cursed to live forever and spend that sad eternity in a small room without internet access would bother to spend time discussing. But since we're on the subject, yes of course it's genre fiction, albeit of a very elevated type, which is to say the narrative is firmly in the fantasy mold but there's more to it then the usual 'wouldn't it be great if I was the chosen one, and no one at work could ever yell at me, and I had a pretty girlfriend.' I quite liked it – written with a lovely fairy tale style in which things don't quite make sense but somehow come together all the same, using a fascinating hybrid of Arthurian myth and pseudo-history, relevant to topics both political personal, sad, beautiful, mysterious, and with some fabulous sword fights. Really, really good sword fights. I like the idea of Ishiguro off in some remote English village and thinking, hmmmmm, what would a fight like this look like, and how would the duel progress, and the different stances, and so on. Definitely worth picking up.

The Black Envelope by Norman Manea – I've written before in this space about how foolish it is to decide a book is bad because you didn't understand it, and more generally of the terrible (and terribly frequent) error in imagining that no one could possibly be smarter than you are. Black Envelope is a difficult novel to review, in so far as despite a serious, determined effort, large portions of it remained essentially obscure to me. Part of that is deliberate – to the degree that there is a plot, large portions of it are never explained, nor does it come to any sort of concrete resolution. Likewise, the reader is obviously meant to be experiencing, to some limited degree, the same feelings of frustration, futility, and lingering madness are as the characters, laboring beneath the oppressive regime of Romanian communism. Still--is it fair to complain about a book being too gnomic, when that is so clearly the author's intent? If so, then I am hereby officially complaining about it. What I got of the book did not make me sufficiently enthusiastic to give it a second reading which might have clarified more of it. Or to put it another way – there is surely something of value here, but you are almost certainly not going to be the one to find it.

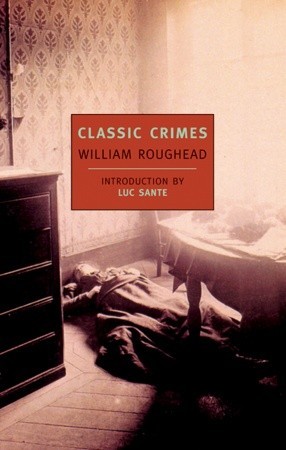

Classic Crimes by William Roughhead – So this was a lot of fun. A collection of true-crime essays, mostly from the 19th century, mostly taking place in Glasgow. Roughhead writes in a style which is at once erudite and readable, and anyone who enjoys outdated slang will have a field day here; I particularly enjoyed Swarfed, meaning fainted, and Kitchen Fee, referring to the ends of leftover food given away to the poor as charity. The crimes are morbid, cruel, and fascinating, lovers poisoning each other slowly with arsenic, the brutal murder of a brother by her half-sister, and Roughhead's discussion of the court cases these crimes give rise to, the frequent incompetence and occasional excellence of the investigators, the fearless disinterest of the accused, the brilliance of some or other lawyer, are a pleasure to read. Recommended if you have any interest in this sort of thing at all.

The Nimrod Flipout: Stories by Etgar Keret – My second collection of Keret's short stories has made me a believer, this guy is the truth. A series of strange, sad, funny short stories, rarely amounting to more than five or ten pages, almost every one of which is a gem. Keret has a real feel for the young male psyche, and many of the stories in this book amount to examinations of masculinity through the lens of a fantastical premise. I hesitate to discuss any of them in detail because they are so brief that a thumbnail sketch serves to ruin the punchline, but suffice to say it is magical realism at its best, using an absurd premise to effectively observe or comment on some aspect of human existence. Keret succeeds in creating entire worlds in very short spaces, doing more with a handful of paragraphs than many writers do with entire novels. Absolutely worth checking out.

The Duel by Casanova – I've never ready any portion of Casanova's biography, though this brief snippet, recalling a pistol duel he fought with a Polish noble while in exile from his native Venice, really made me want to check the entire thing out. It reads like an amoral adventure novel, with the added joy of Casanova's well-earned cynicism about the world and the sad, proud, stupid, creatures who inhabit it.

Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi– A fun little children's story, differing from the Disney version we're all familiar with in so far as Pinnochio begins the story as a horrible little bastard, only gradually improving as a result of his frequent, largely self-inflicted misfortunes. Like all good fantasy, nothing in it ever makes sense, but it doesn't make sense in an entirely understandable way, if you can dig it. I'll read it to my nephew when he's old enough to sit sill for five minutes at a time.

Bunny Lake is Missing by Merriam Modell – The story of a young, single mother in New York, desperately trying to convince the police and various other (male) authorities that her young daughter has been kidnapped, three-quarters of the way through I was ready to anoint this book a work of genius. Sharp, tautly written, disturbing in the extreme, leaving the reader less and less certain about the mental state of the protagonist, making us uncomfortable with our inability to trust her. If this has been a work of 'literature', that is to say, not initially intended as a mass market paperback, and therefore a book which needed to work itself into a comfortable narrative framework, I imagine the author might have felt more comfortable dropping us off a cliff at the climax. Alas, it being what it was the whole thing wraps up in a way which is at once a) absolutely incoherent and b) entirely in keeping with the traditional gender norms which the rest of the book implicitly and explicitly subverts. Read the first 150 pages and then go do something else.

The Door to Bitterness by Martin Limon – Yeah, not bad. There's an unfortunate tendency to herald crime novels in foreign settings simply for being based in an area which the reader might be unfamiliar with (see the atrocious Mapuche, most of Scandanvian noir, etc.), at the expense of narrative, characterization, etc. But everything here is serviceable is not exceptional, and the set-up – the heroes are military police in the US army stationed in South Korea in the 60's – is legitimately interesting. I'd pick up another if I found one.